Opinion: comedy and coping with school shooting drills

As I’ve gotten older, the drills have stayed the same, but the attitude around them has changed. After all, we’ve been doing this for our entire lives.

As code red drills have started and continued with the current generation, students have developed coping mechanism to deal with them.

Dec 12, 2022

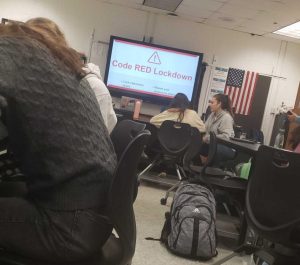

I’ve dealt with Code Red drills throughout my entire life; I was born in 2005 and Columbine happened in 1999. When Sandy Hook happened, I was eight. School shootings became a “tragedy from afar” on the news for my generation, something we think would never happen to us. Our only connection to the atrocities on the evening news was sitting down with our backs to the wall in the dark once a semester, if that. For the last few years, it’s started out the same. First comes the blank screen, then the automated voice and then the darkness.

In my old schools, we used to have a loud, beeping noise that would give me migraines and red flashing lights that could blind you if you looked at them for too long. I’ve been to schools in New York, in Illinois, to Kansas and Southern Georgia. Some parts of the drill are different between the different schools I’ve gone to; other things are exactly the same. We lock the door and sit in the corners, we listen for footsteps and gunshots in the halls.

But one part of these safety drills in particular that has stayed the same and has even grown more prominent in years is the laughter and jokes that swell within the quiet.

Our generation has developed a unique, and often dark humor in response to these school shootings, a humor that only increases in use when events like unexpected drills or lockdowns happen.

Example? The jokes.

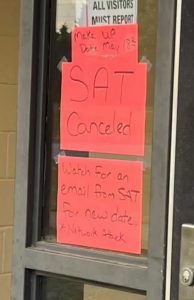

From the numerous TikToks about the “quiet kid,” to the memes that have spawned all over Reddit, to the whispered jokes in the dark to faint sound of sirens, remembering exactly how those sirens had helped the kids of Uvalde and Parkland. It’s why nowadays, instead of keeping silent in the dark, it’s more common to hear laughter and someone going “I guess this means we don’t have a quiz today.”

We’re told to be quiet. To take this seriously. And I don’t think adults understand that these jokes have been born out of fear and an adaptation to the times we live in.

If we joke about a terrible thing, that helps it become less terrifying in our eyes, and helps us process it. Laughter, after all, is the best medicine.

Our generation is not wrong for feeling this way. We are not the ones in charge of lockdowns or gun control laws. We are not the ones teaching children how to hide from assault weapons.

We do not have a say in whether or not we live or die in Algebra class.

We are, however, the ones who face the consequences of inaction.

And yes, there are organizations such as March for Our Lives that are working towards meaningful change, and there has been legislation pushing for gun control, such as the ban on bump stocks, but the fact remains that children of my generation and younger will still have to do Code Red drills. This threat still remains.

So is it any real surprise that we developed our own gallows humor? Is it any surprise that my generation, a generation who has lived under a war, through a recession and within a global pandemic, has decided to cope with this threat the only way they can?

Though this may sound harsh, it seems like a cycle. A school shooting happens, everyone is outraged, promises of action are made, but months go by and nothing has been set in stone. Rinse and repeat, the same thing happens. We have increased drills, our parents get emails and we hope we are never the ones with our school pictures on the evening news.

And while I understand that some adults might find this humor distasteful, that my generation should be hiding under desks instead of trying to lighten the mood, there is nothing more terrifying than preparing to take a quiz, seeing the board go blank and hearing the teacher go, “We weren’t supposed to have a drill today.”

I was rummaging through my bag when the lockdown started on Dec. 2. I couldn’t find my phone. I didn’t know where my brother, a sophomore here, was. I didn’t know what was going on. I couldn’t contact my family.

So we commiserate with our peers, rather than the people who never had to grow up under the threat of an assault rifle, unlike the generations older like Gen X or Baby Boomers. We will be more comfortable with the kids who understand rather than the adults who don’t.

So, yes. My generation, a generation whose school years were shaped by the tragedies of Columbine and Sandy Hook, have been further marred by the horrors of Uvalde and Parkland, Oxford, Santa Fe, Marysville-Pilchuck, by the shootings at Virginia Tech and Umpqua, UC Santa Barbara, Northern Illinois, Oikos University and West Nickel, have taken a different way of coping with this trauma than is accepted.

Perhaps, the message isn’t to tell children to not make jokes, but to understand why these jokes exist in the first place.