A bibliophile finds inspiration in “the brick”

Believe it or not, classic literature (even a 1000-page long novel nicknamed for building materials) still matters today.

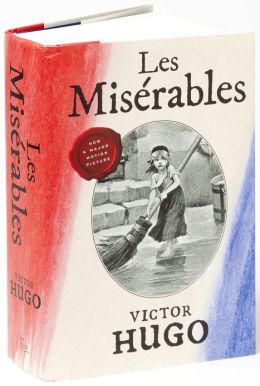

Just over one year ago, there was a (completely understandable) spike in popularity for Victor Hugo’s 1862 tour de force “Les Misérables.” Of course, the majority of the attention was directed to Director Tom Hooper’s nearly three hour long film adaptation of the immensely successful musical version of the novel, but either way, the uproar introduced me to the thousand page book and I couldn’t be more pleased with the outcome.

Now I find myself 450 pages into the second longest book that I have ever read (after “Atlas Shrugged” by Ayn Rand, which I tackled in the second semester of junior year) and at this critical juncture in the plot, I feel the need to share a bit of the genius that has inspired such an extensive and self-revitalizing industry.

(If you fear plot spoilers, then I must recommend that you change your reading material by the time you reach the parenthesis that will most likely follow shortly after the end of this sentence. Here’s another sentence to give you more time to escape. Ready?)

The brilliance of “Les Miserables” (or “Les Miz” if, like me and much of the rest of America, you’d be too embarrassed to try to pronounce the whole thing) lies in the complexity of the characters. The lover of Fantine, a character not seen in any musical or film version to date, is young yet disfigured by premature aging, he is exciting and full of romantic notions but impossible to predict and ultimately leaves the tragic Fantine to raise their child as a single mother. Fantine herself was renowned for her angelic beauty and innocence but is destroyed by the aforementioned Tholomyés and a hostile society that is uncomfortably situated with passionate supporters for anarchy, Napoleon’s dictatorship, and the restored monarchy all trying to control France. She trades the very things that defined her physical beauty for the hope of giving her daughter a better life, not knowing that the little girl is a slave for the novel’s most chaotically evil characters, the Thérnardiers. Even the unnamed figures have back stories that fill chapters. Hugo gives each character a depth that resembles reality: no one is ever good or evil, we all have a bit of both in us.

Through a series of events that read like divine intervention, things begin to click into place for the miserable group of people who give the book its forceful title. Men sneak into and out of convents, Parisian college students complain about the government, Police officers hold extraordinary grudges, and women try to find where they fit in between the rock of their faulty society and the hard place of their gender’s social situation. Yet despite the seemingly exaggerated scale of the story, every passage somehow manages to simultaneously break and mend whatever heart is passing through.

Hugo’s message is one of hope and compassion. Without both, humanity could never have gotten this far. Without both, it will never get any further. It’s as simple as that.

Your donation supports the student journalists of McIntosh High School. Your contribution allows us to cover our annual website hosting costs, to help pay printing costs for "Back to Mac" magazine, and continuing education for staff, such as SNO trainings and MediaNow! editorial leadership training.