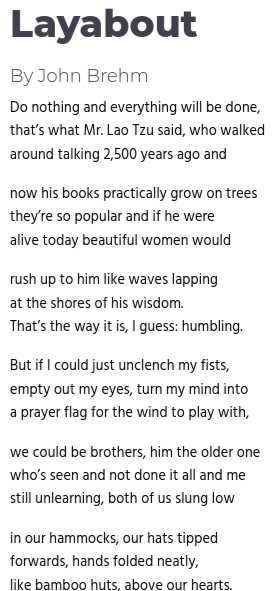

The poem Layabout by John Brehm uses a first person point of view to convey how the youth still finds admiration and inspiration in ancient history but struggles with contemporary life as individuals. The narrator’s tone establishes Mr. Lao Tzu as a mentor, or rather an important figure that Brehm uses to compare the narrator’s struggle to. In the face of the modern world, Layabout focuses on the importance of recognizing how little significance one singular person holds and to enjoy every aspect of life for what it is.

The poem begins by celebrating the freedom and tranquility of “do[ing] nothing and everything will be done,” in a world that glorifies productivity and busyness. Daoist philosopher, Lao Tzu emphasized his principle of wu-wei (nonintervention) and the notion of spontaneous order; simply that people become harmonious by themselves without being ordered to do so (1). Chapter 57 of Lao Tzus’ book Tao Te Ching, sums up the root of his liberal beliefs similar to 18th century liberals stating that “Through my non-action, men are spontaneously transformed. Through my quiescence, men spontaneously become tranquil. Through my non-interfering, men spontaneously increase their wealth’,”. Brehm uses Lao Tzus’ philosophy metaphorically to compare the beauty in relaxation during moments free from pressure and responsibility to governments limiting the free will of its people. In the modern world, these moments to the youth are often forgotten about and looked over by our daily life. However this is described as humbling for the narrator because what the youth fails to remember is that “everything will be done,” or to be vague, life will sort itself out so take a breather (1).

Despite being humbled, the “but” indicates the narrators’ shift in tone from admiration to envy. Brehm uses imagery in portraying how the concept of taking a break from productivity is what the youth yearn for but the fundamental human desire to create lingers. “If I could just unclench my fists, empty out my eyes, turn my mind into a prayer flag for the wind to play with,” demonstrates how contemporary life has infiltrated the youths’ hunger in following the footsteps of ancient mentors, who render qualities that seem in short supply in the fast, fragmented, reality of contemporary life (10-13). The youth are inspired but lack the will power to create because they struggle knowing what to do with their inspiration. Having a spark but no energy to ignite the flame is ironic because Lao Tzus’ message highlights how maintaining peace within yourself is fundamental for prosperity. It is possible the narrator finds solace in Lao Tzus’ philosophy because ancient history provides a fragmented reality of modern age.

The last sentence “But if I could just unclench my fists, empty out my eyes, turn my mind into a prayer flag for the wind to play with, we could be brothers, him the older one who’s seen and not done it all and me still unlearning, both of us slung low in our hammocks, our hats tipped forwards, hands folded neatly, like bamboo huts, above our hearts,” conveys a sense of humility and transience. It speaks to the fleeting nature of life and human values highlighting that while ancient accomplishments may seem monumental, they are ultimately impermanent. This line suggests that rather than idolize/clinging onto the past, the youth should embrace the value in the present and find value in experiencing life for themselves. It aligns with Brehms’ message of finding meaning in simplicity and accepting the natural course of time where even what seems enduring is impermanent.