Is there a Social Dilemma we need to talk about?

Oct 11, 2020

The new Netflix documentary, “The Social Dilemma”, is trying to show people the root problem that social media has placed on today’s society through the eyes of its creators.

“The Social Dilemma” switches between the narrative of a young teenager named Benjamin and documentary style interviews with experts in the technology field. What makes this documentary different from other news outlets and stories talking about the dangers of social media is the credibility of the people speaking. We hear from many experts that span from the creator of the infinite scroll, Aza Raskin, to a Medical Director of Addiction Medicine, Dr. Anna Lembke.

Depression. Suicide. Anxiety. Jonathan Haidt, PhD, a social psychologist and author brings up how social media has made a significant increase on all of these things today. Suicide rates have gone up 70% for teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19 compared to the average made from 2001-2010. Even more troubling, that same number has gone up nearly 151% for girls between the ages of 10-14. This drastic uprise in suicide all surrounds the year 2009, when social media was made available on mobile devices. The way social media has affected young girls today is displayed in the drama portion of the film through the lens of Isla. Isla is a pre-teen girl that is struggling with comparing herself to others on social media, and seeking the approval of her peers on what looks like Instagram. We see her feeling of inadequacy when she re-edits a photo on an Instagram-like platform in order to get more likes, only to get disappointed when someone calls her ears too big.

While the story of Benjamin overall falls a little on the bland side, it does have something unique going for it. Even though our protagonist is unaware of it, there is a small team of people in his phone all working together to get Benjamin to spend as much time as possible on his device. This is supposed to represent the hundreds of computers underground or underwater that are made to track our data, and use that data to make social media more addicting. According to Justin Rosenstein, former engineer of Google and Facebook and the co-founder of Asana, “[The computers] are deeply interconnected with each other, and running extremely complicated programs, sending information back and forth between each other all the time. And they’ll be running many different programs, many different products on those same machines. Some of those things can be described as simple algorithms, some of those things can be described as algorithms that are so complicated you could call them intelligence.”

Most people grew up without social media and cell phones, but there is now a new generation of teenages that are now being brought up with it. Generation Z is spending time in social media during some of the most definitive moments of their lives. “We’re training. Conditioning whole new generations that when we are uncomfortable, or lonely or uncertain, or afraid, we have a digital pacifier for ourselves,” explains Tristan Harris, former design ethicist at Google and co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology. “These technology products were not designed by child psychologists who are trying to protect and nurture children,” furthers Harris. “They were just designing to make these algorithms that were really good at recommending the next video to you, or the really good at getting you to take a photo with the filter on it.”

This thought is furthered with the explanation of how the world connects today. “We’ve created an entire global generation of people who were raised within a context, with the very meaning of communication, the very meaning of culture is manipulation,” says Jaron Lanier. “We’ve put deceit and sneakiness at the absolute center of everything we do.” Jaron Lanier is known as the founding father of virtual reality, a computer scientist, and an author.

Many people will argue that social media is just something new that we as a society will overcome and adapt to. The difference between the two is that with a newspaper, the newspaper is the product. With social media, we are the product. “Because we don’t pay for the products that we use, advertisers pay for the productors that we use,” explains Raskin, “Advertisers are the customers, we’re the thing being sold.” Tristan Harris sums it up pretty well for us: “The classic saying is: ‘If you’re not paying for the product, then you are the product.’” To further this point Roger McNamee, an early investor in Facebook and venture capitalist, compares the Silicon Valley of today, to the Silicon Valley of the past. “The first 50 years of Silicon Valley, the industry made products, hardware, software, sold to the customers. Nice simple business,” McNamee says. “For the last 10 years the biggest companies of Silicon Valley [are] businesses selling their users.”

All of these points that I have made above are really great. But the real question we all have is: “What do we do now?” Many people try to point out the flaws in the world, or in social media, without ever trying to come up with a solution. What makes “The Social Dilemma” different, is that they actually give us a practical solution that doesn’t involve deleting social media. They acknowledge that social media is here to stay, and that just deleting it is not an option. Social Media is just going to get smarter and smarter, and get better and better at predicting what keeps us on our devices. Harris says, “The attention extraction model is not how we want to treat human beings.” Harris believes that in order to stop this model from going on, it starts with holding the big social media companies accountable for the domains that they have taken over. Harris says, “I think we have to have the platforms responsible for when they take over election advertising, they’re responsible for protecting elections. When they take over the mental health of kids or Saturday morning, they’re responsible for protecting Saturday morning.”

“We can demand that these products are designed humanely,” says Harris. “We can demand to not be treated like an extractable source. The intention could be: ‘How do we make the world better?’”

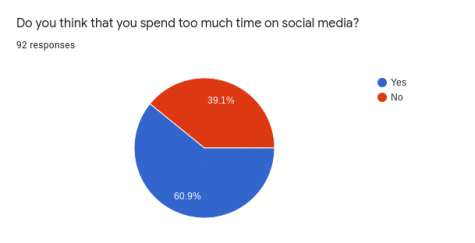

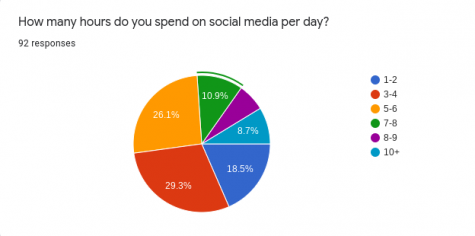

How many hours per day do the McIntosh Chiefs really spend on their phone?